Today I saw an interesting method of holding and tilting the football on a 60 yard field goal attempt. (successful). Is this the new science of holding? Makes sense eh? Forward tilt. Fingers behind so there is no resistance. Interesting. (to me)

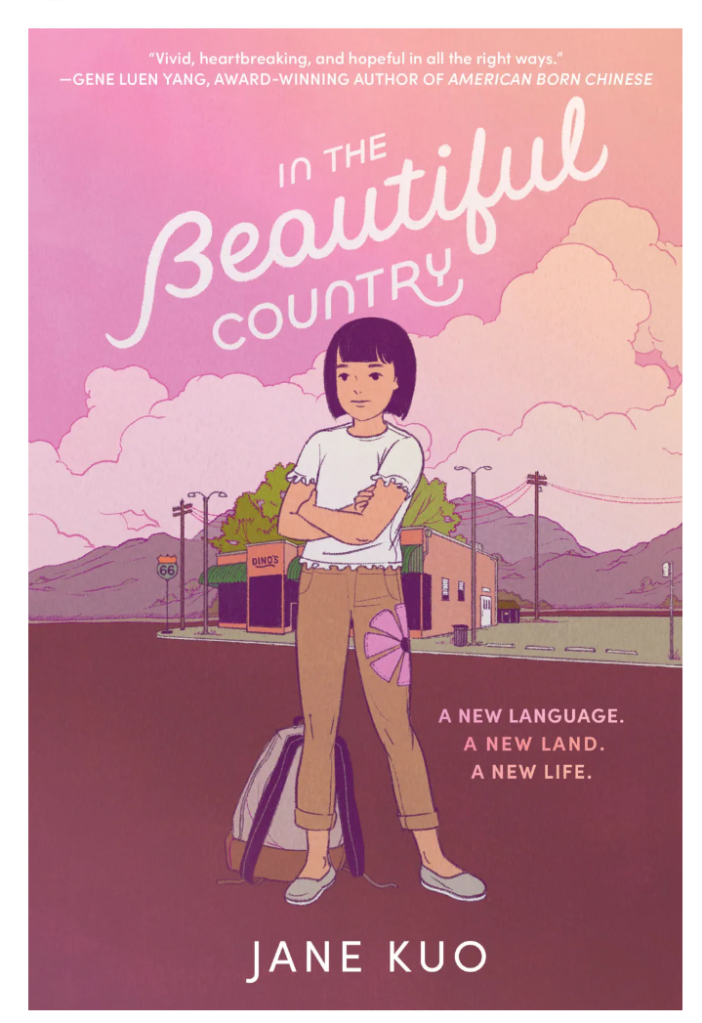

Today I read A Beautiful Country, by Jane Kuo. I was in search of a children’s book and couldn’t put it down. I wish I could find the right superlatives to do justice to my feelings about it at this moment. I loved it. Smartly conceived. Elegantly crafted. Poignant. I really like what the author pulled off here.

by Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer

Today I heard A.E. Stallings give her first lecture as the Oxford Professor of Poetry in November of 2023:

https://podcasts.ox.ac.uk/bat-poet-poetry-echolocation

Having taken the on-ramp to these lectures by first listening to a smattering of these lectures delivered by Geoffrey Hill, Simon Armitige, and Alice Oswald before coming to Stallings, I must say that her American’ness was jarring, at first. I had become used to operating the shifter with my left hand, and then suddenly traffic is zipping by dangerously on what somehow feels like the wrong side of the road. (discombobulating) I kept thinking “please don’t embarrass us, please don’t embarrass us” where, by us, I meant U.S.

Then I thought, oh shit, she’s awesome, and totally embarrassing U.S. (lol), but not really, but kind of, but no, but yes, but not at all. I then thought of how American she must seem to the majority of the room, and how the high-brow portion of the audience might be feeling. In the background, I kept thinking of her journey to this point. A girl educated in a small rural community outside of Athens GA, becomes a scholar of Greek literature and a poet and is now occupying this position at Oxford. What an American dream story; rags to riches.

Then she came into her own, in the mid-point of her lecture, — or perhaps I settled down– and her fearless small town American girl authenticity just shone through and was completely delightful. I was pleasantly amused at how she mimicked, poorly, –because she probably thought, should I really be doing this?–a stuffy English male accent as she read some piece. I was wide-eyed when one of her asides was: “It’s a terrifying poem, I mean, I feel bat-shit crazy reading this poem”. I think it was a contrived statement that she set aside, but decided to pull in at that moment, which made it sound nicely spontaneous and funny, and yet I could not hear even a titter from the audience. Why was that?

In the end, with her blah blah blah and her yadda yadda yadda, and her digs at Robert Frost etc., she knocked all the English stuffing out of me, and by the end, brought me to literal tears.

Before listening to this, her first lecture, I did take in just a few minutes from the lecture that came after this, and was saying to myself, “no no no… this is not good, this won’t do”. It all felt too nonchalant, as if I was looking in on a 300 level mid-semester course where the bell was going to ring at any moment and she would be yelling out the homework assignments as the kids streamed out the doors into the hallway. But now that she has won me over, with lecture number 1, I shall approach lecture 2 with a better understanding of her “jizz” (birder terminology) and hopefully find communion.

A lecture by Professor Sir Geoffrey Hill of Oxford on March 10, 2015:

The most exciting part of the lecture, for me, comes around the 18:43 mark when Geoffrey begins to speak at length about the “O” and “Oh” in poetry, which I, for a long time, (as some may know) have had a stormy relationship with.

This is the 2nd lecture of Professor Hill’s that I have listened to. He’s confident, cantankerous, humorous, and pronounces a lot of words wrong.

Here is the page where the lectures are found. I’ve emailed Oxford to ask why two are unavailable.

I didn’t know anything about Goeffrey Hill or these lectures until I was assigned to listen to some of the lectures of past Oxford Professor’s of Poetry by Dr. Timothy Bartel, in preparation for a deeper discussion on the appointment of the first American to the post, A.E. Stallings; who, go figure, lives in Greece.

Lyrics

She’s got a smile that it seems to me

Reminds me of childhood memories

Where everything was as fresh as the bright blue sky

Now and then when I see her face

She takes me away to that special place

And if I stare too long, I’d probably break down and cry

Whoa, oh, oh

Sweet child o’ mine

Whoa, oh, oh, oh

Sweet love of mine

She’s got eyes of the bluest skies

As if they thought of rain

I’d hate to look into those eyes and see an ounce of pain

Her hair reminds me of a warm safe place

Where as a child I’d hide

And pray for the thunder and the rain to quietly pass me by

Whoa, oh, oh

Sweet child o’ mine

Whoa whoa, oh, oh, oh

Sweet love of mine

Whoa, yeah

Whoa, oh, oh, oh

Sweet child o’ mine

Whoa, oh, whoa, oh

Sweet love of mine

Whoa, oh, oh, oh

Sweet child o’ mine

Ooh, yeah

Ooh, sweet love of mine

Where do we go?

Where do we go now?

Where do we go?

Ooh, oh, where do we go?

Where do we go now?

Oh, where do we go now?

Where do we go? (Sweet child)

Where do we go now?

Ay, ay, ay, ay, ay, ay, ay, ay

Where do we go now?

Ah, ah

Where do we go?

Oh, where do we go now?

Oh, where do we go?

Oh, where do we go now?

Where do we go?

Oh, where do we go now?

Now, now, now, now, now, now, now

Sweet child

Sweet child of mine

A mountain hamlet in northern Japan claims Jesus Christ was buried there

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-little-known-legend-of-jesus-in-japan-165354242/

Smithsonian Magazine

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Rising-Son-Japan-Jesus-631.jpg)

On the flat top of a steep hill in a distant corner of northern Japan lies the tomb of an itinerant shepherd who, two millennia ago, settled down there to grow garlic. He fell in love with a farmer’s daughter named Miyuko, fathered three kids and died at the ripe old age of 106. In the mountain hamlet of Shingo, he’s remembered by the name Daitenku Taro Jurai. The rest of the world knows him as Jesus Christ.

It turns out that Jesus of Nazareth—the Messiah, worker of miracles and spiritual figurehead for one of the world’s foremost religions—did not die on the cross at Calvary, as widely reported. According to amusing local folklore, that was his kid brother, Isukiri, whose severed ear was interred in an adjacent burial mound in Japan.

A bucolic backwater with only one Christian resident (Toshiko Sato, who was 77 when I visited last spring) and no church within 30 miles, Shingo nevertheless bills itself as Kirisuto no Sato (Christ’s Hometown). Every year 20,000 or so pilgrims and pagans visit the site, which is maintained by a nearby yogurt factory. Some visitors shell out the 100-yen entrance fee at the Legend of Christ Museum, a trove of religious relics that sells everything from Jesus coasters to coffee mugs. Some participate in the springtime Christ Festival, a mashup of multidenominational rites in which kimono-clad women dance around the twin graves and chant a three-line litany in an unknown language. The ceremony, designed to console the spirit of Jesus, has been staged by the local tourism bureau since 1964.

The Japanese are mostly Buddhist or Shintoist, and, in a nation of 127.8 million, about 1 percent identify themselves as Christian. The country harbors a large floating population of folk religionists enchanted by the mysterious, the uncanny and the counterintuitive. “They find spiritual fulfillment in being eclectic,” says Richard Fox Young, a professor of religious history at the Princeton Theological Seminary. “That is, you can have it all: A feeling of closeness—to Jesus and Buddha and many, many other divine figures—without any of the obligations that come from a more singular religious orientation.”

In Shingo, the Greatest Story Ever Told is retold like this: Jesus first came to Japan at the age of 21 to study theology. This was during his so-called “lost years,” a 12-year gap unaccounted for in the New Testament. He landed at the west coast port of Amanohashidate, a spit of land that juts across Miyazu Bay, and became a disciple of a great master near Mount Fuji, learning the Japanese language and Eastern culture. At 33, he returned to Judea—by way of Morocco!—to talk up what a museum brochure calls the “sacred land” he had just visited.

Having run afoul of the Roman authorities, Jesus was arrested and condemned to crucifixion for heresy. But he cheated the executioners by trading places with the unsung, if not unremembered, Isukiri. To escape persecution, Jesus fled back to the promised land of Japan with two keepsakes: one of his sibling’s ears and a lock of the Virgin Mary’s hair. He trekked across the frozen wilderness of Siberia to Alaska, a journey of four years, 6,000 miles and innumerable privations. This alternative Second Coming ended after he sailed to Hachinohe, an ox-cart ride from Shingo.

Upon reaching the village, Jesus retired to a life in exile, adopted a new identity and raised a family. He is said to have lived out his natural life ministering to the needy. He sported a balding gray pate, a coat of many folds and a distinctive nose, which, the museum brochure observes, earned him a reputation as a “long-nosed goblin.”

When Jesus died, his body was left exposed on a hilltop for four years. In keeping with the customs of the time, his bones were then bundled and buried in a grave—the same mound of earth that is now topped by a timber cross and surrounded by a picket fence. Though the Japanese Jesus performed no miracles, one could be forgiven for wondering whether he ever turned water into sake.

This all sounds more Life of Brian than Life of Jesus. Still, the case for the Shingo Savior is argued vigorously in the museum and enlivened by folklore. In ancient times, it’s believed, villagers maintained traditions alien to the rest of Japan. Men wore clothes that resembled the toga-like robes of biblical Palestine, women wore veils, and babies were toted around in woven baskets like those in the Holy Land. Not only were newborns swaddled in clothes embroidered with a design that resembled a Star of David, but, as a talisman, their foreheads were marked with charcoal crosses.

The museum contends that the local dialect contains words like aba or gaga (mother) and aya or dada (father) that are closer to Hebrew than Japanese, and that the old village name, Heraimura, can be traced to an early Middle Eastern diaspora. Religious scholar Arimasa Kubo, a retired Tokyo pastor, thinks Shingo may have been settled by “descendants of the ten lost tribes of Israel.”

As if to fuel this unlikely explanation, in 2004, Israeli ambassador Eli Cohen visited the tombs and dedicated a plaque, in Hebrew, to honor the ties between Shingo and the city of Jerusalem. Embassy spokesman Gil Haskel explained that while Hebrew tribes could have migrated to Japan, the marker was merely “a symbol of friendship rather than an endorsement of the Jesus claims.”

Another theory raises the possibility that the tombs hold the bodies of 16th- century missionaries. Christian evangelists first came to Japan in 1549, but bitter infighting for influence and Japanese converts led to a nationwide ban on the religion in 1614.

Believers went underground, and these Hidden Christians, as they are called, encountered ferocious persecution. To root them out, officials administered loyalty tests in which priests and other practitioners were required to trample a cross or an image of the Madonna and the baby Jesus. Those who refused to denounce their beliefs were crucified, beheaded, burned at the stake, tortured to death or hanged upside-down over cesspools to intensify their suffering. For more than 200 years, until an isolated Japan opened its doors to the West in 1868, Christianity survived in scattered communities, which perhaps explains why Shingo’s so-called Christian traditions are not practiced in the rest of the region.

The key to Shingo’s Christ cult lies in a scroll purported to be Christ’s last will and testament, dictated as he was dying in the village. A team of what a museum pamphlet calls “archeologists from an international society for the research of ancient literature” discovered the scripture in 1936. That manuscript, along with others allegedly unearthed by a Shinto priest around the same time, flesh out Christ’s further adventures between Judea and Japan, and pinpoint Shingo as his final resting place. (As luck would have it, the graves of Adam and Eve were just 15 miles west of town.)

Curiously, these documents were destroyed during World War II, the museum says, allowing it to house only modern transcriptions—signed “Jesus Christ, father of Christmas”—inside a glass case. Even more curiously, Jesus lived during Japan’s Yayoi period, a time of rudimentary civilization with no written language.

The original scrolls were brought to Shingo by an Eastern magi that included the Shinto priest, a historian and a charismatic Christian missionary who preached that the Japanese emperor was the Jewish Messiah. They were joined by Shingo Mayor Denjiro Sasaki, a publicity hound eager to make the town a tourist destination. Sasaki led them through a valley of rice fields and up a slope to a bamboo thicket that concealed the burial mounds. For generations, the land had been owned by the garlic-farming Sawaguchis.

One of the clan, a youth named Sanjiro, was renowned for his blue eyes, something seldom seen in Japan and, as nationalist historian Banzan Toya insisted, proof that the Sawaguchis were progeny of Jesus and Miyuko, who, to complicate matters even more, is variously known as Yumiko, Miyo and Mariko. Among the magi’s other extravagant finds were seven ancient pyramids, all of which were said to predate the ones built by the Egyptians and the Mayans by tens of thousands of years. The heap of rocks generously dubbed the Big Stone God Pyramid is just down the road from the Christ tomb. Miraculously, the historian and the priest stumbled upon the rubble a day after they stumbled upon the graves. A sign beside this Shinto sanctuary explains that the pyramid collapsed during a 19th-century earthquake.

Shinto is a religion of nature, and during the imperialist fervor that gripped Japan before World War II, its message of Japanese uniqueness was exploited to bolster national unity. “Religious organizations could only operate freely if they had government recognition,” says Richard Fox Young.

Out of this constraint came “State Shinto”—the use of the faith, with its shrines and deities, for propaganda, emperor worship and the celebration of patriotism. Considerable resources were funneled into attempts to prove the country’s superiority over other races and cultures. Which sheds celestial light on the discovery of Moses’ tomb at Mount Houdatsu in Ishikawa Prefecture. Press accounts of the period detailed how the prophet had received the Hebrew language, the Ten Commandments and the first Star of David directly from Japan’s divine emperor.

Such divine condescension implies that Shingo’s Christ cult has very little to do with Christianity. “On the contrary,” says Young. “It’s more about Japanese folk religion and its sponginess—its capacity for soaking up any and all influences, usually without coherence, even internally.”

That sponginess is never more evident than during Yuletide, a season that, stripped of Christian significance, has taken on a meaning all its own. It’s said that a Japanese department store once innocently displayed Santa Claus nailed to a crucifix. Apocryphal or not, the story has cultural resonance.

Shingo is modestly festive with frosted pine trees and sparkling lights, glittering streamers and green-and-red wreaths, candles and crèches. In Japan, Christmas Eve is a kind of date night in which many young people ignore the chaste example of Mary—and instead lose their virginity. “It’s the most romantic holiday in Japan, surpassing Valentine’s Day,” says Chris Carlsen, an Oregon native who teaches English in town. “On Christmas Day, everyone goes back to work and all the ornaments are taken down.”

Junichiro Sawaguchi, the eldest member of the Shingo family regarded as Christ’s direct descendants, celebrates the holiday much like the average Japanese citizen, in a secular way involving decorations and Kentucky Fried Chicken. A City Hall bureaucrat, he has never been to a church nor read the Bible. “I’m Buddhist,” he says.

Asked if he believes the Jesus-in-Japan yarn, Sawaguchi shakes his head and says, coyly, “I don’t know.” Then again, notes Carlsen, the Japanese tend to be quite tactful when airing their opinions, particularly on contentious topics. “The Christ tomb has given Shingo a sense of identity,” he says. “If a central figure like Mr. Sawaguchi were to dismiss the story, he might feel disloyal to the town.”

But does Sawaguchi think it’s possible that Jesus was his kinsfolk? Momentarily silent, he shrugs and spreads his palms outward, as if to say, Don’t take everything you hear as gospel.

The Closing of the Bulgarian Frontier

wasting away in the prison of timelessness

anything but the broth!

I really enjoyed this. Thank you to “The Browser”